Mastication does the body good, according to an article in September 2007 Fitness (p.106):

Medical studies have found that chewing sugar-free gum for 20 minutes a day can:

-Help you burn 11 calories an hour which is equivalent to 11 pounds of body fat each year

-Help you suppress hunger

-Help blood flow to the brain, increasing your memory

-Help relieve stress...50% of study participants agree!

-Help neutralize plaque acids after eating, keeping cavities at bay

Right, fellow Alchemists, we all know that we need to power our bodies with energy, or calories, in order to stay focused, think clearly, be active, and productive. So why is it then that many religions require at least some time spent fasting, or abstaining from food--often for periods of 24 hours or more? How does that make sense to having a healthy and productive outlook?

There is no doubt that you begin to feel light-headed in the first twelve hours: your blood sugar begins to dip and you notice that you cannot stay on task or concentrate. In another five hours, the hunger pangs almost cease, your body resigning itself to the fact that you are not going to feed it yet, and it becomes more difficult to perform physical tasks; your balance, like your head, is not able to come into focus.

By the time you reach 24 full hours with no food, you are sapped of energy, though not completely, and you are almost used to the light-headedness. But you DO feel a survival urge, an instinctive push, to eat--not because you feel terribly hungry anymore, that fades away--but because your body is beginning to tap into your fat stores, and so, you are going into a physical minimalist state.

This is what science and medicine tells us, and it is true. Mentally, or spiritually (whatever you prefer), you begin to feel it much sooner--the "it" I refer to is that minimalism--or what Lacan called the Real. We're never really so in touch with the Real as when we strip ourselves of the essentials. Our body and mind--the two entagled like the sub-atomic particles in quantum mechanics--are one, indistinguishable from one another during such an entaglement, feeding each other, or, sapping each other's energy:

According to psycho-onocological studies, cancer patients who feel emotionally supported (and eat well and exercise, of course) live an average of six years longer than those who feel hopeless and helpless.

Stress, caused by an increase in emotional anxiety stemming from certain social situations such as employment, family or friends, releases cortisal into the body. In November 2006, the journal, Cancer Research reported that an increase in cortisal can nt only cause cancer, bu can help it to grow. Cortisal contains several compounds that both feed cancer cells, and help them to spread or metastasize.

Science is backing up what we already know: Your mind and your body affect each other, though seemingly indistinguishable--they are two separate entities in a virtual entaglement. Now, it's time for the philosophy.

Fasting is meant to give a human being the opportunity to grow--you are no longer restricted by your body's needs and can better immerse yourself in the needs of the mind, or, if you will, the spirit. During a fast, you are forced to consider what is truly important in your life, what needs improvement, and how to implement (once you're eating again) strategies to make it all happen. Fasting encourages deep introspection--something western society sorely lacks in the midst of digital cable, internet, jobs, sports, malls, restaurants, movies, plays, and the list goes on and on and on....

Fasting, though, should be limited to not more than once or twice a year--it does take a toll on the body, which we know then takes a toll on the mind as well. However, when we do fast, we should use it for its intended purpose, breaking down the drudgery of daily life and seeking ways to change for the better, thereby improving all of society.

There is a theological metaphor about how each person who lives represents a strand of webbing, all interconnected, like a spider's web. When one strand is damaged, the integrity of the web as a whole is affected. As I sit here fasting, now in my 22nd hour, I can't help but begin to see that though we each function as individuals, we, like our bodies and minds, are in a sort-of entanglement as well.

Humans require companionship--it's hard-wired, and is the basis for all civilizations. If we all know this, as acknowledged by the many countries, cities, towns, all over Earth, how is it then that we continue to disrupt the human web? As an individual, it can feel rather hopeless to try to affect change, to help others see that there are no boundaries, cultural, theological, geographical, visual, physical, or otherwise, in this, our human equation. Helplessness follows, and then, we seek to fill that emotional gap however we can--leading to further our social estrangement in a slow decay.

And somehow, this must cease. If we could each take a day to refocus ourselves, to truly examine who we are, not just as individuals, but in the scope of our global society, perhaps that sense of hopelessness and helplessness would get a bit better, sending a positive ripple throughout each person's life, the world over. Our society, like the cancer patients in the psycho-onocological studies, will "live" longer....

Parmenides, an holistic Greek philosopher (circa 500 AD) said, "All is one. Nor is it divisible, wherefore, it is wholly continuous."

It is the 21tst century. As a society, we need to catch up to Parmenides from the past. We are all one, part of a social entaglement; there are perceived divisions but we can just as easily un-perceive those separations. We will not continue as a society, as a global community, unless more time is spent on considering what is truly Real.

Until we next meet, fellow Alchemists, move carefully through your given space, remembering that coincidences do not exist....

Wow...The Science (and Philosophy) of Fasting

Alchemy with Gold

Alchemy Articles

Alchemy: Then and Now

Ruth Kassinger--The Washington Post--March 22, 1999

Sir Isaac Newton: mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist.

Yes, the man who invented calculus and derived the law of universal gravitation also practiced alchemy, the ancient and secretive pseudo-science of turning base metals into gold. Newton spent years working at his furnace with dangerous and smelly combinations of the raw materials of alchemy -- mercury, silver, lead and sulfur.

He was convinced that not only could gold be made but also that ancient alchemists had done so. Their secret knowledge, he believed, although largely lost, might be teased from 2,000 years of accumulated ancient Greek, Egyptian and Arab writings, many of which he had read and copied.

After one experiment, Newton wrote in an unpublished manuscript that he thought he had the "great secret of Alchemy," a sort of "living" mercury that "makes gold begin to swell . . . . and also to spring forth in sprouts and branches." The process didn't pan out, but the secret, he felt, was nearly within his grasp.

It wasn't. But mercury can, indeed, be turned into gold. The secret lies in understanding the structure of the atom's nucleus and the technology of accelerating atomic particles. That knowledge wouldn't arrive, however, until 250 years after Newton and 20 centuries after alchemists first sought the recipe for gold.

WHY GOLD?

Gold is soft enough to cut with a knife, so it has never been useful as a material for tools. Although its malleability makes it easy to shape into jewelry, it also dents and scratches easily, which is why even a high-quality, 18-karat "gold" ring is 25 percent other metals.

Gold is extremely heavy. A gold bar is twice as heavy as the same-sized bar made of lead. After plundering Persia of its gold in 334 B.C., Alexander the Great decided to bury portions of the treasure along the trail to lighten the burden on his soldiers. Nonetheless, many early civilizations treasured gold and silver for its value as ornamentation.

But about 3500 B.C., when people in the new towns of ancient Mesopotamia began to use the metals as money to facilitate trade, gold and silver took on new value. Until then, families were largely self-sufficient in food and bartered for foodstuffs or objects that they didn't grow or make.

But as more people lived in towns and became less self-sufficient, the need to trade increased. Instead of accepting a herd of goats in exchange for his cloth and then trading the goats for the sheep he really wanted, a craftsman could accept silver and, knowing that his neighbors valued the silver as he did, buy sheep directly.

At first, the gold and silver were traded in chunks that merchants had to weigh, but by about 2800 B.C., Mesopotamians had formed it into rings of standard weights.

Gold didn't tarnish like copper or silver or rust like iron and wasn't damaged by heat. In fact, until medieval alchemists concocted the acid known as aqua regia, gold was considered indestructible.

Moreover, gold is rare, about six times rarer than silver. On average, to extract an ounce of gold from Earth's crust, one must smash and process about three tons of rock. People who held their wealth in gold did not often find their riches suddenly diluted by appearance of a large new supply.

The desirability of gold has always been enhanced by associations that people make with it. Because it seemed imperishable, the ancient Chinese thought that gold might convey its immortality to its owners. Gold coins reminded people of the golden sun with its warming, life-giving qualities.

Bernard Trevisan, a medieval Italian alchemist, wondered, "Is not gold merely [the sun's] beams condensed to a solid yellow?" Anthropologist Kaj Arhem notes that the Makuna people of Brazil believe that "gold contains the light of the sun and stars."

AN ANCIENT PEDIGREE

Newton and many of his contemporaries, including chemist Robert Boyle and philosopher John Locke, were among the last of a long line of intellectuals who believed in alchemical transmutation of base metals.

The Adam of the lineage was Aristotle. He believed that all materials in the physical world were made of four elements -- water, earth, air and fire -- and that the proportion of the elements in any substance determined what the substance was.

Although he never tried to prove it, Aristotle predicted that one material could be transformed into another by altering the mix of its elements.

He also believed, as did most people of the time, that metals grew in the ground, like plants, although much more slowly. Just as seeds grew into more "perfect" plants and children grew into more "perfect" adults, so all metals eventually would attain the ideal form of metals, gold, he believed.

When Alexander the Great marched into Egypt, he took the ideas of his tutor, Aristotle, with him. The Egyptians drew on sophisticated goldsmiths' techniques and other chemical knowledge gained in glassmaking and dyeing to try putting Aristotle's ideas to practical use.

Through elaborate mixing and heating procedures, they attempted to make gold by changing the proportion of elements in base metals or hurrying "natural growth" of these metals into gold.

One of the earliest alchemists whose identity has survived was a Jewish woman who is known as "Marie," lived in Egypt about 100 A.D. and conducted experiments with mercury, which was tantalizing silver-colored, and sulfur, whose yellow hue seemed related to gold.

In her work, she invented several devices for heating her ingredients. One is used today -- the double-boiler, known in French as a bain-Marie, or "Marie's bath."

By 300 A.D., perhaps from lack of success, Egyptian alchemists turned increasingly to mystical approaches. Zosimos, whose recipes sometimes came to him in dreams, wrote that "the soul of copper must be purified until it receives the sheen of gold and turns into the royal sun-metal."

The mystics' recipes, filled with symbols based on magic and astrology, would intrigue alchemists until Newton's time.

ALCHEMY DISSOLVED

After Egypt came under Roman control with the defeat of Cleopatra in the 1st century B.C., alchemy did not fare well.

Diocletian, emperor of Rome from 284 to 305 A.D., ordered destruction of all Egyptian alchemical writings, concerned that alchemists' gold would fund a rebellion.

When Constantine made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire in the middle of the 4th century, alchemy and other Hellenistic thought was suppressed for its pagan associations. However, many of the forbidden manuscripts were saved by a sect of dissident Christians, called Nestorians, who took them to Persia about 400.

Between 640 and 720, followers of the prophet Mohammed conquered an empire that stretched from India to Spain and included Egypt. Arab alchemists, too, adopted Aristotle's ideas, from Nestorians and Egyptians.

During crusades to Jerusalem in the 12th century, Europeans rediscovered the store of alchemical and other classical works by Arabs. To the mix of Aristotelian philosophy, Egyptian mysticism and the Arabs' practical chemical knowledge, Europeans added concepts of religious transformation from Christianity.

If bread and wine could change into the body and blood of Christ, some alchemists thought that, with God's help, a man of pure spirit might turn lead to gold. Because the Roman Catholic Church came to support Aristotle's basic ideas, with an added role for God, alchemy no longer was anathema. In fact, many European alchemists of the medieval era were clerics.

APPARENT SUCCESS

It may seem odd that alchemy survived for so many centuries without producing gold. One reason is that the early alchemists believed they had done so.

One ancient Egyptian recipe for "diplosis" (doubling) of gold called for a heated mixture of two parts gold with one part each of silver and copper. Indeed, twice as much of a golden material results.

Egyptian alchemists believed that the gold acted as a seed in the copper and silver. The seed grew, eating the copper and silver as food, until the whole mixture was full-grown gold. Today, we know that, because the silver gives the gold a greenish tint and the copper gives it a reddish tint, mixing both hardly changes the color of the gold.

Early alchemists also believed that they were making gold because, at the time, it wasn't clear what gold was. Gold found in nature often is combined, or alloyed, with other minerals or metals, so the standard for gold was imprecise. If a metal looked like gold and felt like gold, it might as well be gold.

Even when people knew that what looked like gold actually could be a mix of gold and another metal, it was difficult to determine whether a sample was pure gold.

A hard, black stone known as a touchstone was an ancient device for determining the quality of gold. Scraping a piece of gold across it left a streak of gold. Depending on the brightness of the streak, an expert could estimate how much gold was in the sample. Unfortunately, a touchstone wasn't precise and couldn't determine whether the gold was only a coating on a metal of lesser value.

As early as 1500 BC, Mesopotamians discovered a method for purifying gold called "cuppellation," which involved heating impure gold in a porcelain cup called a cuppel. Impurities were absorbed by the porcelain, leaving a pure gold button.

Later alchemists used cuppellation to prove that their transmutations were successful. They would put lead on which they had experimented into the cuppel and heat it.

When a small bit of gold appeared in the bottom, they wrote in all good faith that their alchemy worked, citing the bit of gold as evidence that the lead was on its way to becoming all gold. They didn't know that most lead ore has a little gold or silver in it. That was what they had found.

Alchemists also were encouraged by amazing substances they did make, including nitric, hydrochloric and sulfuric acids. With a hiss and some smoke, these ate through all kinds of metals.

In about 1100, alchemists made aqua regia, a combination of nitric and hydrochloric acids that could destroy gold. Alchemists assumed that the ability to destroy gold would be followed quickly by their ability to create it.

THE NEW ALCHEMY

Alchemists, of course, never could make gold. Gold is an "element," a substance composed entirely of one kind of atom and not further divisible by chemical processes into other kinds of atoms.

Not until the late 18th century, when chemists Joseph Priestly, Henry Cavendish and Antoine Lavoisier experimented with air and fire, did it became clear that some substances are elements and others are compounds. Compounds are made of two or more elements. Water, for example, is a combination of hydrogen and oxygen.

Throughout the 19th century, through experimentation, scientists compiled a growing list of elements.

Just before World War I, British physicist Ernest Rutherford and others developed a model of the atom as composed of a nucleus containing a tightly bound cluster of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons and surrounded at a distance by orbiting, negatively charged electrons.

In an electrically neutral atom, the number of electrons is equal to that of protons.

Why couldn't alchemists transform one element into another?

An atom of any element is determined by the number of protons in its nucleus. The simplest atom, hydrogen, has one positive proton in its nucleus and one negative electron circling it. The element with two protons is helium, and the element with three protons is lithium.

In the nucleus of an atom of gold are 79 protons and 79 electrons. Changing one element into another requires changing the number of protons in the nucleus, a very difficult procedure.

Any proton aimed at a nucleus is repulsed by the positive charge of the nucleus. The only way to insert a proton is to sling it with enough energy to overcome that electrical repulsion.

In 1919, Rutherford bombarded nitrogen atoms, with their seven protons and seven neutrons, with alpha particles. These are helium nuclei containing two protons and two neutrons. The helium protons penetrated the nucleus of the nitrogen atoms and produced an isotope of oxygen (eight protons and nine neutrons) and hydrogen (one proton). Rutherford was first to transmute an element successfully.

Still, the transmutation was not entirely man-made. Rutherford worked his magic by taking advantage of naturally occurring radioactivity to achieve the energy to break into a nucleus.

In 1932, British physicists J. D. Cockcroft and E.T.S. Walton developed a device for accelerating protons and aimed a beam of protons at a sample of lithium. One more proton joined lithium's nucleus of three protons and four neutrons, which transmuted into two atoms of helium, each with two protons and two neutrons. This was the first time anyone had transmuted one element into another artificially.

To be sure, new information and high technology were required to achieve what alchemists had attempted for 2,000 years. But a different approach to knowledge also was needed. We now call it the scientific method, whereby experiment must confirm all ideas.

Failure of their experiments did not make alchemists question the ideas. They assumed that they had not fully understood the ideas or had failed to follow the recipe accurately.

John Maynard Keynes, the English economist who collected Newton's alchemical notes and manuscripts, called Newton "the last of the magicians" who saw the world as a sort of philosopher's treasure hunt with clues scattered about in the evidence of the heavens and in obscure writings and traditions passed through the ages.

MAN-MADE GOLD

Today, scientists use much more powerful accelerators and can accelerate nuclear particles with 1 million times the energy of the device used by Cockcroft and Walton.

In the late 1960s, Judith Temperley, a physicist at Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, studied properties of various metals by bombarding them with high-energy neutrons.

In one experiment, the target metal was mercury, an element with 80 protons. Under these conditions, a neutron enters the nucleus, which ultimately causes destruction of a proton by a process called "electron capture." The result is an atom with only 79 protons, making it an atom of gold!

So the alchemists were correct: A base metal can be turned into gold, but only with extreme patience. Accumulate a penny's worth of gold from mercury in this fashion, says Barry L. Berman, a physicist at George Washington University, will take about 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years.

TOP HERBAL SLEEPING

Every once in a while I get sleeping problems, and this time I have decided to find some natural herbal remedies to help. Here's my top 10 of herbal sleeping remedies:

1. Valerian (Lat. Valeriana officinalis) - this is the first herbal remedy used to cure insomnia, as well as stress and anxiety. It also purports to improve the quality of sleep. However, valerian is only a long-term aid. For best results, it should be used regularly for at least one month to benefit from its effects. Valerian can be used as a tea or extract. Research has shown that valerian is at least as potent as diazepam or variants (see here).

2. Lavender (Lat. l. angustifolia) - it has a general tranquillizing and relaxing effect on the body, which induces sleep. Lavender can be used as a tea, relaxing oil (to be rubbed into muscle areas), or for aromatherapy purposes.

3. Passion Flower (Lat. passiflora) - it acts as an internal relaxer, promoting the gentle functioning of the body, particularly the digestive system. Like valerian, it is best to be used regularly to enhance its benefits. Passion flower is typically used as a tea, although pills can be found.

4. Hops (humulus lupulus) - it is a typical component of beer. Hops are a natural sedative which is often combined with chamomile, lavender or valerian.

5. Chamomile (matricaria camomilla) - it is used 'on the spot' to relax and help restful sleep. Usually brewed as a tea and drank before bedtime.

6. Lemon Balm (melissa officinalis) - it has sedative action and can be brewed as a pleasant-tasting tea.

7. Kava (piper methysticum) - it is highly potent for anxiety relief. It can usually be found as an extract or as a spray to be used under the tongue.

8. Lime / linden flower (tilia cordata) - it is used to calm headaches, anxiety and to promote sleep by relaxing muscles. It makes a very pleasant-tasting tea.

9. Chaste tree - recent studies have shown that chaste tree increases the natural production of melatonin in the body (the hormone that instigates sleep). I don't know that much about this one, but I will be looking into it.

10. Honey - well, ok, not a herb per se, but in combination with the other herbs it helps promote sleep.

Many of these herbs can be mixed into potent sleeping teas: for instance, valerian is often combined with hops and lemon balm. The best advice is to look into the contents of sleeping teas you buy if you do not make one yourself.

Alchemical Symbols

Alchemic symbols, originally devised as part of the protoscience of alchemy, were used to denote some elements and some compounds until the 18th century. Note that while notation like this was mostly standardized, style and symbol varied between alchemists, so this page lists the most common.

Three Primes

According to Paracelsus, the Three Primes or Tria Prima are:

* Sulfur (omnipresent spirit of life)

* Mercury (fluid connection between the High and the Low)

* Salt (base matter)

Four basic Elements

* Fire

* Water

* Earth

* Air

RESPECTIVELY

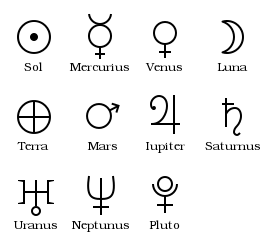

Seven Planetary Metals

Planetary metals were "dominated" or "ruled" by one of the seven planets known by the ancients. Although they occasionally have a symbol of their own (denoted by also:), they were usually symbolized by the planet's symbol.

* Gold dominated by Sol ☉ ☼ ( )

* Silver dominated by Luna ☽ ( )

* Copper dominated by Venus ♀ (also: )

* Iron dominated by Mars ♂ ( )

* Tin dominated by Jupiter ♃ ( )

* Mercury (quicksilver) dominated by Mercury ☿ ( )

* Lead dominated by Saturn ♄ ( )

The planets Uranus and Neptune and the dwarf planet Pluto were discovered after the time alchemy had been largely replaced by chemistry, and are not part of traditional Alchemical symbols. Some modern alchemists consider the symbols for these planets to represent the radioactive metals uranium, neptunium and plutonium, respectively. Also, the Monas Hieroglyphica is an alchemical symbol devised by John Dee as a combination of the plantery metal glyphs.

12 Core Alchemical processes

The 12 Alchemical processes are considered to be the basis of modern chemical processes. Each of these processes is "dominated" or "ruled" by one of the 12 Zodiac signs.

* Decomposition through Oxidation (Aries )

* Decomposition through Digestion (Leo )

* Decomposition through Fermentation/Putrefaction (Capricorn)

* Modification through Congelation/Coagulation (Taurus )

* Modification through Fixation (Gemini )

* Modification through Ceration (Sagittarius )

* Separation through Distillation (Virgo )

* Separation through Sublimation (Libra )

* Separation through Filtration (Scorpio )

* Union through Solution (Cancer )

* Union through Multiplication (Aquarius )

* Union through Projection (Pisces )

Alchemical Symbols

Alchemic symbols, originally devised as part of the protoscience of alchemy, were used to denote some elements and some compounds until the 18th century. Note that while notation like this was mostly standardized, style and symbol varied between alchemists, so this page lists the most common.

Three Primes

According to Paracelsus, the Three Primes or Tria Prima are:

* Sulfur (omnipresent spirit of life)

* Mercury (fluid connection between the High and the Low)

* Salt (base matter)

Alchemy in Islam

Alchemy and chemistry in Islam refers to the study of both traditional alchemy and early practical chemistry (the early chemical investigation of nature in general) by Muslim scientists in the medieval Islamic world. The word alchemy itself was derived from the Arabic word الكيمياء al-kimia.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the focus of alchemical development moved to the Arab Empire and the Islamic civilization. Much more is known about Islamic alchemy as it was better documented; indeed, most of the earlier writings that have come down through the years were preserved as Arabic translations.[1]

The study of alchemy and chemistry often overlapped in the early Islamic world, but later there were disputes between the traditional alchemists and the practical chemists who discredited alchemy. Muslim chemists and alchemists were the first to employ the experimental scientific method (as practised in modern chemistry), while Muslim alchemists also developed theories on the transmutation of metals, the philosopher's stone and the Takwin (artificial creation of life in the laboratory), like in later medieval European alchemy, though these alchemical theories were rejected by practical Muslim chemists from the 9th century onwards.

The Islamic world was a melting pot for alchemy. Islamic alchemists such as Jabir ibn Hayyan (Latinized as Geber) and the Persian alchemist Razi (Latinized as Rasis or Rhazes) contributed key chemical discoveries, including:

* Distillation apparatus (such as the alembic, still, and retort) which were able to fully purify chemical substances.

* The words elixir, alembic and alcohol are of Arabic origin.

* The muriatic (hydrochloric), sulfuric, nitric and acetic acids.

* Soda and potash.

* Distilled water and purified distilled alcohol.

* Perfumery

* Many more chemical substances and apparatus.

* From the Arabic names of al-natrun and al-qalīy, Latinized into Natrium and Kalium, come the modern symbols for sodium and potassium.

* The discovery that aqua regia, a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids, could dissolve the noblest metal, gold, was to fuel the imagination of alchemists for the next millennium.

Islamic philosophers also made great contributions to alchemical hermeticism. The most influential author in this regard was arguably Persian Jabir Ibn Hayyan (جابر بن حيان, Latin Geberus; usually rendered in English as Geber). He analyzed each Aristotelian element in terms of four basic qualities of hotness, coldness, dryness, and moistness.[2] According to Geber, in each metal two of these qualities were interior and two were exterior. For example, lead was externally cold and dry, while gold was hot and moist. Thus, Jabir theorized, by rearranging the qualities of one metal, a different metal would result.[3] By this reasoning, the search for the philosopher's stone was introduced to Western alchemy.[4][5] Jabir developed an elaborate numerology whereby the root letters of a substance's name in Arabic, when treated with various transformations, held correspondences to the element's physical properties.

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed by Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber). His original system consisted of seven elements, which included the five classical elements (aether, air, earth, fire and water), in addition to two chemical elements representing the metals: sulphur, ‘the stone which burns’, which characterized the principle of combustibility, and mercury, which contained the idealized principle of metallic properties. Shortly thereafter, this evolved into eight elements, with the Arabic concept of the three metallic principles: sulphur giving flammability or combustion, mercury giving volatility and stability, and salt giving solidity.[6]

Muslim alchemists also developed theories on the transmutation of metals, the philosopher's stone and the Takwin (artificial creation of life in the laboratory), like in later medieval European alchemy, though these alchemical theories were rejected by practical Muslim chemists from the 9th century onwards.

An early experimental scientific method for chemistry began emerging among early Muslim chemists. The first and most influential was the 9th century chemist, Geber (Jabir ibn Hayyan), who is "considered by many to be the father of chemistry",[7][8][9][10] for introducing:

* The experimental method; apparatus such as the alembic, still, and retort; and chemical processes such as liquefaction, purification, oxidisation and evaporation.[10]

* Crystallisation.[7]

* The chemical process of filtration.[11]

* Pure distillation[11] (impure distillation methods were known to the Babylonians, Greeks and Egyptians since ancient times, but Geber was the first to introduce distillation apparatus and techniques which were able to fully purify chemical substances).

* The distillation and production of numerous chemical substances.

Jabir clearly recognized and proclaimed the importance of experimentation:

"The first essential in chemistry is that you should perform practical work and conduct experiments, for he who performs not practical work nor makes experiments will never attain the least degree of mastery."[12]

The historian of chemistry Erick John Holmyard gives credit to Jabir for developing alchemy into an experimental science and he writes that Jabir's importance to the history of chemistry is equal to that of Robert Boyle and Antoine Lavoisier.[13] The historian Paul Kraus, who had studied most of Jabir's extant works in Arabic and Latin, summarized the importance of Jabir ibn Hayyan to the history of chemistry by comparing his experimental and systematic works in chemistry with that of the allegorical and unintelligble works of the ancient Greek alchemists:[14]

“To form an idea of the historical place of Jabir’s alchemy and to tackle the problem of its sources, it is advisable to compare it with what remains to us of the alchemical literature in the Greek language. One knows in which miserable state this literature reached us. Collected by Byzantine scientists from the tenth century, the corpus of the Greek alchemists is a cluster of incoherent fragments, going back to all the times since the third century until the end of the Middle Ages.”

“The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers, among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz , von Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugiere and others, could make clear only few points of detail…

The study of the Greek alchemists is not very encouraging. An even surface examination of the Greek texts shows that a very small part only was organized according to true experiments of laboratory: even the supposedly technical writings, in the state where we find them today, are unintelligible nonsense which refuses any interpretation.

It is different with Jabir’s alchemy. The relatively clear description of the processes and the alchemical apparatuses, the methodical classification of the substances, mark an experimental spirit which is extremely far away from the weird and odd esotericism of the Greek texts. The theory on which Jabir supports his operations is one of clearness and of an impressive unity. More than with the other Arab authors, one notes with him a balance between theoretical teaching and practical teaching, between the `ilm and the `amal. In vain one would seek in the Greek texts a work as systematic as that which is presented for example in the Book of Seventy.”

Jabir's teacher, Ja'far al-Sadiq, refuted Aristotle's theory of the four classical elements and discovered that each one is made up of different chemical elements:

"I wonder how a man like Aristotle could say that in the world there are only four elements - Earth, Water, Fire, and Air. The Earth is not an element. It contains many elements. Each metal, which is in the earth, is an element."[15]

Al-Sadiq also developed a particle theory, which he described as follows:

"The universe was born out of a tiny particle, which had two opposite poles. That particle produced an atom. In this way matter came into being. Then the matter diversified. This diversification was caused by the density or rarity of the atoms."[15]

Al-Sadiq also wrote a theory on the opacity and transparency of materials. He stated that materials which are solid and absorbent are opaque, and materials which are solid and repellent are more or less transparent. He also stated that opaque materials absorb heat.[15]

Al-Kindi, who was a chemist and an opponent of alchemy, was the first to refute the study of traditional alchemy and the theory of the transmutation of metals into more precious metals such as gold or silver.[16] Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī,[17] Avicenna[18] and Ibn Khaldun were also opponents of alchemy who refuted the theory of the transmutation of metals.

Another influential Muslim chemist was al-Razi (Rhazes), who in his Doubts about Galen, was the first to prove both Aristotle's theory of classical elements and Galen's theory of humorism wrong using an experimental method. He carried out an experiment which would upset these theories by inserting a liquid with a different temperature into a body resulting in an increase or decrease of bodily heat, which resembled the temperature of that particular fluid. Al-Razi noted particularly that a warm drink would heat up the body to a degree much higher than its own natural temperature, thus the drink would trigger a response from the body, rather than transferring only its own warmth or coldness to it. Al-Razi's chemical experiments further suggested other qualities of matter, such as "oiliness" and "sulfurousness", or inflammability and salinity, which were not readily explained by the traditional fire, water, earth and air division of elements.[19] Al-Razi was also the first to:

* Distill petroleum.

* Invent kerosene and kerosene lamps.

* Invent soap bars and modern recipes for soap.

* Produce antiseptics.

* Develop numerous chemical processes such as sublimation.

In the 13th century Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī stated an early version of the law of conservation of mass, noting that a body of matter is able to change, but is not able to disappear.[20]

From the 12th century, the writings of Jabir, al-Kindi, al-Razi and Avicenna became widely known in Europe during the Arabic-Latin translation movement and later through the Latin writings of a pseudo-Geber, an anonymous alchemist born in 14th century Spain, who translated more of Jabir's books into Latin and wrote some of his own books under the pen name of "Geber".

Alchemy Introduction

Alchemy (Arabic:al-kimia) (Hebrew:אלכימיה al-khimia) is both a philosophy and a practice with an aim of achieving ultimate wisdom as well as immortality, involving the improvement of the alchemist as well as the making of several substances described as possessing unusual properties. The practical aspect of alchemy generated the basics of modern inorganic chemistry, namely concerning procedures, equipment and the identification and use of many current substances.

The fundamental ideas of alchemy are said to have arisen in the ancient Persian Empire.[1] Alchemy has been practiced in Mesopotamia (comprising much of today's Iraq), Egypt, Persia (today's Iran), India, China, Japan, Korea and in Classical Greece and Rome, in the Muslim civilizations, and then in Europe up to the 20th century, in a complex network of schools and philosophical systems spanning at least 2500 years.

Alchemy, generally, derives from the Old French alkemie; from the Arabic al-kimia: "the art of transformation." Some scholars believe the Arabs borrowed the word chimia ("χημεία") from Greek for transmutation.[2] Others, such as Mahdihassan,[3] argue that its origins are Chinese.

During the seventeenth century the change of name from Alchemy to chemistry took place, with the work of Robert Boyle, sometimes known as "The father of Chemistry"[citation needed], who in his book "The Skeptical Chymist" attacked Paracelsus and the old Aristotelian concepts of the elements and laid down the foundations of modern chemistry.